(Note: definitely read the follow-up article on this topic, called “California Turns Up the Heat on HFC Refrigerants – Further Clarifications,” especially if you are considering strategy #4 that is listed in the article below. CARB may not agree with me about whether the “use” of pre-purchased, high-GWP virgin refrigerant after 1/1/2025 counts as commerce. As always, you should consult an attorney for legal advice, especially because the slightest detail of your plans can change the legal situation drastically.)

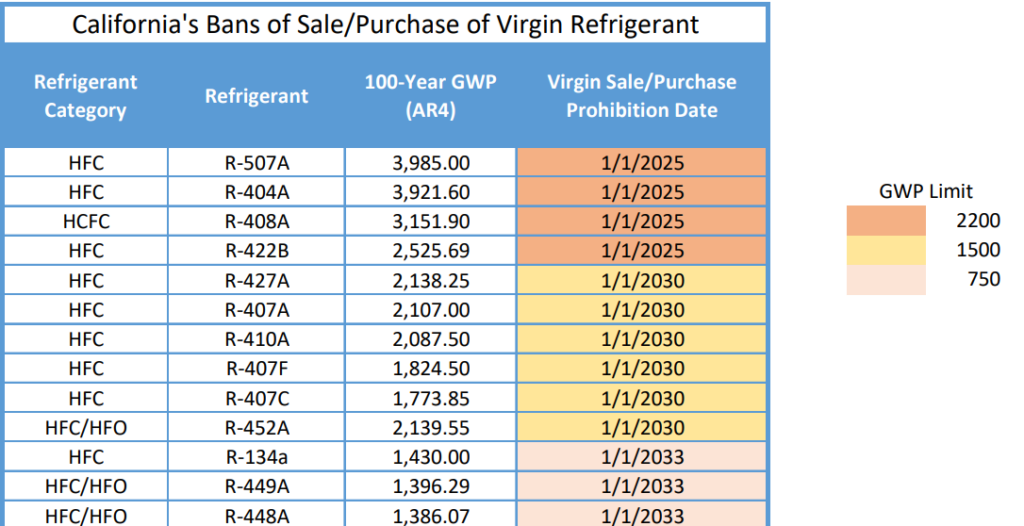

California’s ban on the sale of virgin, bulk HFC refrigerants with GWPs greater than 2,200 goes into effect in just 8 months, on January 1, 2025. This is the first step of a 3-step process that will culminate in the year 2033. These bans aren’t specific to our industry; California’s website states that “SB 1206 would affect all sources that use HFCs which include foams, aerosols, fire suppressants, cold storage warehouses, refrigeration systems, air conditioning and heat pumps.”[1]

Table from the RMS CA Refrigerant Bans Table fact sheet

The text of the regulation is as follows [2]:

- (b)(1) A person shall not offer for sale or distribution, or otherwise enter into commerce in the state, bulk hydrofluorocarbons or bulk blends containing hydrofluorocarbons that exceed any of the global warming potential limits as specified in paragraph (2), (3), or (4).

- (2) Beginning January 1, 2025, the global warming potential shall not exceed 2,200.

- (3) Beginning January 1, 2030, the global warming potential shall not exceed 1,500.

- (4) Beginning January 1, 2033, the global warming potential shall not exceed 750.

The other essential part of the regulatory text for supermarkets is this one:

- (d)(1) The prohibitions established pursuant to subdivision (b) or (c) shall not apply to either of the following:

- (A) Hydrofluorocarbons that are reclaimed.

On the face of it, there are five main strategies for coping with this ban – not counting hope. While I don’t discourage hope in general, I don’t count it as a legitimate strategy for dealing with the consequences of federal or state refrigerant regulations. It may be true that there’s no crying in baseball, but there’s plenty of crying among those who counted on hope as a strategy to prepare for refrigerant regulations.

Strategy #1

Prepare ahead of time and secure your own banked, reclaimed refrigerant. This is probably the safest strategy, because it’s the only strategy that puts your own fate in your own hands. It may be the safest strategy, but I suspect it’s also the rarest strategy.

Strategy #2

Rely on other peoples’ reclaimed refrigerant. This is risky, because there are likely to be a lot of people who didn’t start soon enough to bank their own refrigerant, so everyone is going to be fighting over the HFCs that are available on the reclaim market. As is always the case if there is more demand than supply, the price of reclaimed refrigerant on the open market is likely to be high.

Strategy #3

Retrofit enough of your existing high-GWP systems on a rolling basis to provide yourself with refrigerant to meet your ongoing servicing needs. I know of several food retail companies who dealt with the R-22 phaseout this way. This strategy has its logistical issues, and it involves constant monitoring and tracking of exactly how much refrigerant for servicing you have stored vs. the maximum amount you need for servicing at any point in time. It also means that your company must be able to quickly arrange for a retrofit project every time your supply of refrigerant for servicing runs low. Note that this strategy makes more sense for recycled refrigerant . The regulation stipulates that reclaimed refrigerant is exempt from the ban; it doesn’t mention a recycled refrigerant exemption.

Strategy #4

Purchase a whole bunch of R-404A on December 31st, 2024, and store it (hoard it) for your own use for as long as it lasts. The ban doesn’t say that it is illegal to use refrigerants with global warming potentials >2200 unless your system is a state-owned stationary refrigeration system.

Strategy #5

Replace all your high-GWP systems with systems that use refrigerants that are under the thresholds for the ban.

Lest you think that this all doesn’t apply to you because you don’t buy refrigerants in bulk, think again. The California regulation uses the same definition for bulk refrigerant as the definition in the EPA’s Aim Act regulations (Section 84.3 of Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations):

… a regulated substance of any amount that is in a container for the transportation or storage of that substance such as cylinders, drums, ISO tanks, and small cans. A regulated substance that must first be transferred from a container to another container, vessel, or piece of equipment in order to realize its intended use is a bulk substance. A regulated substance contained in a manufactured product such as an appliance, an aerosol can, or a foam is not a bulk substance.

The EPA gives some examples of things that are bulk and things that aren’t. For instance, an “air conditioning recharge kit is a bulk substance because the contents must first be transferred to realize its intended use.” But … “A regulated substance contained in a manufactured product such as an appliance, an aerosol can, or a foam is not a bulk substance.” And by the way, if you are the type of person who asks the question “which GWP” every time you see the letters G, W, and P together, the law specifies that the GWP thresholds are based on the 100-year global warming potential values.[4]

For those of you shaking your head and thinking how in the world this is all supposed to work, CARB is required to tell you that – unfortunately they don’t have to tell you that until January 1st, 2025, the same day that the ban goes into effect for the highest GWP refrigerants.I don’t know about you, but the language of the law raises several questions in my mind. I am going to attempt to get some answers to these questions from CARB and post a follow-up article. We’ll see how that goes. These are the types of questions that RMS clients typically ask, but they aren’t the types of questions that governments like to answer.[5]

I don’t know about you, but the language of the law raises several questions in my mind. I am going to attempt to get some answers to these questions from CARB and post a follow-up article. We’ll see how that goes. These are the types of questions that RMS clients typically ask, but they aren’t the types of questions that governments like to answer.

The first question that went through my mind is whether it is legal for someone who works for a food retail company to drive from California to a neighboring state, buy virgin R-404A, and then drive back to California and use that virgin refrigerant in the company’s systems. The law states that it is illegal to “offer for sale or distribution, or otherwise enter into commerce in the state … .” In this scenario, the sale and commerce happen outside of California, and the only thing that happens in California is the use.

The second question is if the EPA’s definition of bulk refrigerant does not include refrigerant that is contained “in a manufactured product,” and the EPA defines a product as an appliance that is factory assembled and factory charged, does this ban apply to packaged air-conditioning units and self-contained refrigerated cases?

The third question is whether California truly meant to only exempt reclaimed refrigerant, rather than allowing food retailers to re-use their own unprocessed recovered refrigerant or their own recycled refrigerant in their systems. It would seem that the state would encourage you to re-use your own refrigerant without mandating that you first reclaim it. That would be a win-win for the environment, wouldn’t it?

We’ll see what they say! Until next time …

PS: For those of you who thought my next article would be the second part of the series on the Chronically Leaking Appliance Rule … well, so did I. What can I say? When it comes to writing, if I’m not feeling it, I’m not feeling it. I promise to keep trying.

The information in this article is not intended as legal advice or as a substitute for the particularized advice of your own counsel. Anyone seeking specific legal advice or assistance should retain an attorney.

[1] https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/sb-1206/about

[2] https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces

/billNavClient.xhtml ?bill_id=202120220SB1206

[3] Recycling refrigerant means using your own recovered refrigerant after minimal processing, e.g. running it through a filter drier. It is only legal to use recycled refrigerant in your own systems.

[4] The law specifies that the GWP thresholds are based on the 100-year global warming potential values published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) in 2007, and if a relevant value is not contained in AR4, “global warming potential” means the 100-year global warming potential values published by the IPCC in its Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) in 2013 or as determined by the state board in a regulation adopted pursuant to this section.

[5] The law states that “[t]he state board shall post an assessment on its internet website by January 1, 2025, specifying how to transition the state’s economy, by sector, away from hydrofluorocarbons and to ultra-low GWP or no-GWP alternatives no later than 2035 through maximizing recovery and reclamation and increasing adoption of new low and ultra-low GWP alternative refrigerants.”